Sarah Baartman, the monsterisation of the black female body and its poetics

Initial Inspiration

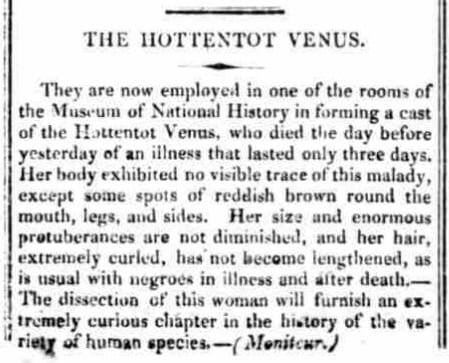

The portrait above is the most realistic likeness of Sarah ‘Saartjie’ Baartman, a Khoi Khoi woman who was exhibited in 19th century Europe as the Hottentot Venus. She is the subject of the first half of my poetry collection, Monster and this image helped me visualise her so that I could reimagine her life in poetry. But I remain conflicted about this image. On the one hand, having a near accurate document of what Baartman looked like adds to the sense of her as a real person who existed in history rather than just as a representation of an idea. On the other hand, the provenance of the image is far from edifying.

In March 1815, Baartman agreed, in the name of science, to pose naked for a study session lasting three days at the Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris led by zoologists Etienne Geoffroy Saint–Hilaire and Georges Cuvier. Saint–Hilaire and Cuvier who is sometimes referred to as the “founding father of palaeontology, scrutinised her physiognomy while artists assigned to the museum - Jean–Baptiste Berré, Léon de Wailly, and Nicolas Huet - sketched her figure. Léon de Wailly’s portraits of Baartman, above and further below, were also reproduced in the form of watercolour illustrations in Saint-Hilaire and Cuvier’s 1819 book Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères. Baartman was the only human being to appear in the book.

The image above is the most innocuous I’ve found of Baartman. Images that follow below depicting her life and the aftermath of her death get progressively more disturbing. I had reservations about displaying these images here just as much as I thought long and hard about creating poetry out of the details of her life. I’m sensitive to the idea of further propagating the indignities that she suffered both in life and after she died. I also wanted to be careful that my refracting of her life through the prism of poetry, did not feel like undue appropriation.

As much as I hesitate to add more notoriety to Baartman’s legacy by sharing these images, I also feel it is important we are fully cognisant of history’s disturbing and pernicious constructions about the black female body. If these images are hidden away, instead of treating them like historical artefacts that can initiate more nuanced interrogation of what history has handed down to us, then we run the risk of playing into the hands of those who would deny the part history has played in perpetuating racism.

Still, a way to ensure responsible use of the images is to put them in a part of my website which can only be accessed via the QR code in my book, Monster.

The Black Female Body on Display

I believe this engraving is the first image I ever saw of Sarah Baartman.

During her lifetime, Baartman captivated scientists, scholars, artists and writers as she continues to do today. Although Baartman, displayed on European stages as the Hottentot Venus between 1810 and 1815 because of her large buttocks, was one of the most famous women in her lifetime, very little is actually known about the person she was.

It was 1996 or 1997 and True Magazine had recently relaunched as Trace Magazine, promising to showcase black creativity in all its variety. I boldly pitched up at its offices somewhere in East London and declared that I was a journalist who wanted to contribute to the publication. Then I had to go away to think up some ideas that would back up my bold claims.

Some years before, when I came to back to England from Ghana aged 17, I used to hang out with a girl called Emma Pitcher at my sixth form college. Gradually, I came to realise that Emma, a white girl, considered herself superior to me. On one occasion, she said “I suppose she’s pretty for black woman” when I expressed admiration for Whitney Houston’s beauty. Another time she told me that my “bottom was so big it was like the sun rising” as I was bending over to pick up something from the floor. Reflecting on this in 2024, I feel sad that my 17 year old self was given such a rude awakening in Eurocentric body shaming.

I knew I had to write about black women’s bottoms for Trace that would also help me metabolise those run-ins with Emma. I hit on the idea of starting the piece with a list working through the alphabet of synonyms for bottom. In the course of researching the article, I stumbled on Sarah Baartman’s sorry story. Many years later, I would transform the article into the second poem I ever wrote, called Bottom Power. Women always tell me that they will never talk down their bodies again after hearing me read the poem but it wasn’t until I performed the poem in Cape Town on a British Council tour of South Africa that the impulse that made me write Bottom Power coalesced into the urge to extend its subject matter into a full poetry collection. Someone in the audience asked me in the Q&A afterwards: “what do you think Saartjie Baartman would say in response if she heard your poem today?” The question floored me because I hadn’t given any thought to it. I couldn’t shake the feeling that I had been remiss not to consider it. So I set out to answer the question and it resulted in Monster.

In the engraving above by an unknown artist whose title translates as “The Curious in Ecstasy”, a practically naked Baartman stands on a box similar to a pedestal in a museum, labelled ‘La Belle Hottentot’. It’s Paris in 1815, civilians and Scottish soldiers ogle Baartman. The crouching woman’s words translate as “something unhappy and good” while the civilian man’s are “what a strange beauty.” The soldier on the right says “Ah! That nature is funny.” The words of the soldier on the left seem to be a part transliteration of English rendered into French that reads as “Oh! Godem, what rosbif.” It’s a matter of speculation as to whether the artist intentionally drew his sword to mimic an erect penis as he reaches out to touch her bottom. Curiously, both soldiers are sexualised, perhaps to pronounce the Hottentot Venus’ so-called primal nature. Ultimately, it contextualises Baartman in her guise of the Hottentot Venus as a hyper-sexualised figure to be gazed at and exclaimed upon, simultaneously entrancing, arousing and paradoxically, repelling. The gaze that fixes her is a voyeuristically desiring but also condemning one.

Almost two centuries before Sarah Baartman arrived in Europe, notions of the feral nature and sexual deviance of black women that justified their objectification, dehumanisation and oppression were widespread across Europe. The painting above entitled Rape of the Negress (sometimes sanitised as Three White Men and a Black Woman) was completed in 1632 by the little-known Delft artist Christiaen van Couwenbergh (1604-1667) and is currently housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Strasbourg. The painting was most likely a private commission from a wealthy individual. What I find particularly disturbing is the emphatically not human way the very dark-skinned woman has been depicted and the superior attitude of the man on the left who is inviting the complicity of the viewer as if he is asking us to be okay with this visual violence perpetrated upon the woman. More troubling is finding out that this painting is often displayed without careful contextualisation in exhibitions today.

Exhibitions, Salons and political cartoons in newspapers

One of the remarkable aspects of Sarah Baartman’s story is how much of a London story it is too. It’s not that far away from us in the grand scheme of the capital’s time - less than two and half centuries - and definitely right under our feet in terms of place. The location of 225 Piccadilly, top of the Haymarket in the flyer above, is what we now call the Criterion Building today. Londoners will recognise it as the building that houses Lillywhites, the store on several floors that sells lots sporting goods and sits right on the corner of Piccadilly Circus.

In Baartman’ time, William Bullock first opened his museum in Liverpool in 1795 whilst trading as a jeweller and goldsmith. The contents, including works of art, natural history objects, armour and curiosities from Captain Cook’s south sea voyages, were relocated to London in 1809 opening initially as the ‘Liverpool Museum’ (the picture below with all the stuffed animals) in the Critireon Building. In 1812 it moved along the road in Piccadilly to the newly built Egyptian Hall. A poem in Monster called Exhibition of a Real Life Wonder (Still Alive!) is inspired by these locations and events.

The two engravings above are French. The first one depicts Sarah Baartman as the Hottentot Venus in the salon of the Duchess du Berry. In it, Baartman is still in the centre of the picture with greatly exaggerated buttocks but this time, she is a more active participant in the action - she seems to be chasing her audience of smartly dressed gentry as the men seem to ward away the blushing women. This time, even though the curiosity of the onlookers is still present, they turn away from her, more repulsed than entranced. Once again, she is semi-naked, a creature that engenders both fear and repulsion, measured against the chaste ‘purity’ of the white women.

Then of course there is the objectification and caricaturisation of Baartman’s body as depicted in the cartoons below.

The 1810 political cartoon by William Heath, above left, shows Baartman standing in profile back to back with Lord Grenville, Prime Minister and leader of the Broad Bottoms coalition government. The playwright Richard Sheridan uses a pair of compasses to measure Baartman's posterior. Grenville, with a paper in his pocket inscribed 'Chanselor says: 'Well I never expected Broad Bottoms from Africa, but one should never despair! Mind Sherry, don't let your Fiery Nose touch the Venus for if there's any Combustibles around here we shall be Blown Up!!!' Sheridan answers, 'I shall be Careful Your Lordship! But such a spanker, it beats your Lordships Hollow!!!'

In the cartoon from the same year on the right, Heath depicts Grenville as dark-skinned as Baartman. Behind Grenville is his elder brother, the Marquess of Buckingham (George Nugent Temple Grenville), wearing spectacles. On the right, behind Baartmann, is Buckingham's son, Lord Temple (Richard Temple Nugent Brydges Chandos, Earl Temple, subsequently Duke of Buckingham and Chandos). The caption reads: ‘Love at first sight, or a pair of Hottentots, with an Addition to the Broad Bottom Family. Lord Grenville says ‘At last I have met with a true Broad Bottom real flesh no deception!!! I wonder if Broad Bottoms would breed in this country’. Sarah Bartmann replies ‘Me hear of your bottom, me long to see it, me write to you about it!!!’ Lord Buckingham says ‘Ah sure a pair were never seen so justly formed to meet by Nature" (a quotation from Sheridan's comic opera The Duenna. Lord Temple says ‘Charming indeed I am so pappy [sic] the family is not extinct’.

Heath is obviously using Baartman as a kind of insult, reducing her to that one physical feature which, as Sheridan’s compass suggests can be measured and classified as a specimen for public spectacle and foreshadows scientific racism.

Freak Shows And Monsters at Bartholomew Fair

As well as being displayed in museums, one-off shows and salons, Sarah Baartman was exhibited at the famous Bartholomew Fair, which was held at Smithfield in London every August, along with other ‘freaks’ of nature. It’s all the research I did around what happened during the fair that inspired the title of my collection, Monster, and several of the poems within the book too:

1. Blues for Sarah

2. Exhibition of a Real Life Wonder (Still Alive!)

3. In Which Comedian Charles Matthews, Actor Charles Kemble and Dandy Beau Brummell Question Miss Sara Baartman Before Her Evening Performance

4. Freak Sonnets for Lusus Naturae at Bartholomew Fair: Natural-Born, Man-Made and Counterfeit

5. Sestina: Six Scientists in Search of an Ology

Freak Sonnets for Lusus Naturae at Bartholomew Fair: Natural-Born, Man-Made and Counterfeit, a sequence of sonnets especially gave me an opportunity to dig into the idea of the monster or the monstrous in juxtaposition with women and femininity. It harks back to Carl Linnaeus’ 5th category of human expression, Homo monstrosus, monstrous creatures who were man-like but with anomalous characteristics who occupied remote areas. Sarah Baartman’s protuberant posterior fit into this category as did a lot of the other human beings displayed in Bartholomew Fair - ‘freaks of nature’ like bearded ladies, people with dwarfism, extremely tall people, albinos, conjoined twins etc.

There’s certainly a preoccupation in the book with the monstrous as a constructed status. But who are the constructors of this status? It tends to be people with societal power, usually men, in government, academia, religion etc. Although I didn’t consciously intellectualise all of that during the composition of the book, it has seeped into the poetry anyway.

The lustful gaze of scientific rationalism

Baartman died in the last days of December 1815, on the 29th, 30th or 31st depending on the sources, perhaps of smallpox, pneumonia or excessive drinking, and the police headquarters authorised the transport of her corpse to the Jardin des Plants where George Cuvier, Europe’s most esteemed proponent of comparative anatomy, would made a plaster cast of her corpse then dissected her body for his scientific purposes. A few years later, he published his findings in Histoire Naturelle des Mammiferes. Baartman is the only human entry in a book full of monkeys and other mammals. In this way, Baartman was defined by a white colonist epistemology which purported to ‘know’ her while also keeping its distance to ‘see’ what they wanted, fixing her in an image that still has ramifications for the way that black women are portrayed today.

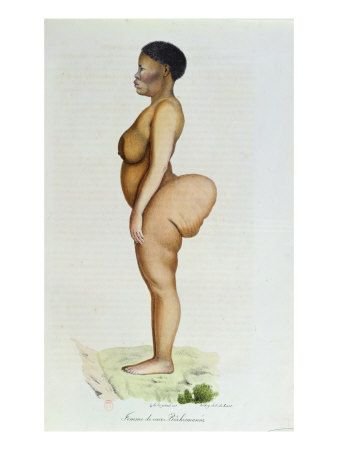

These two illustrations of Sarah Baartman are taken from Histoire Naturelle des Mammifères by zoologists Etienne Geoffroy Saint–Hilaire and Georges Cuvier.(1819). The depiction of Baartman was accompanied by the caption “Femme de race Bôchismanne.” She was the only the human being featured in a book otherwise containing mostly four legged animals (see the 4 images below). Cuvier’s descriptions of the illustrations also positioned Baartman closer to the animal in the evolutionary scale by comparing her with the mammals pictured in the book. It was a typical example of the quintessence of the “black woman” offered to the fantasies of the European coloniser, a concept that has attained a stickiness that persists into the 21st century.

Where, Europeans wondered, did the Hottentot Venus fit in the natural order of things? Many believed the Hottentot Venus was more ape than human or that she represented a fifth category of human, a Homo sapiens monstrous, a kind of Frankenstein’s monster scarcely capable of emotion and intelligence yet also a reminder to Europeans of the primitive living deep within the self.

It was not enough to theorise that black female sexuality was animalistic. In a quest for concrete proof, Cuvier excised Baartman’s hypertrophied vaginal labia - called at the time the ‘Hottentot apron’ - and enlarged buttocks which were typical of the physiognomy of the Khoikhoi. For 19th century audiences, these physical specificities were the external indicators of black women’s ‘primitive’ sexuality. Cuvier “proved” the otherness of Sarah Bartmann; he showed her as deformed in comparison to white French women and reaffirmed the domination of the white, male European scholar over black women.

For Cuvier, Baartman’s sudden and unpredictable movements were similar to a monkey’s, and her way of protruding her lips were supposedly were what he’d observed an orang-utan do. Baartman therefore entered the Western imagination as a transitional link between man and beast, a simulacrum rather than a person full of emotions and memories, desires and specific sensibilities. This is the thing that stuck with me the most when I set out to write Monster. I was struck by the fact that although there has been so much written about her, both in her lifetime and in the historical aftermath of her death, none of those words are her own direct speech. So that question that I was asked on a Cape Town stage - “what do you think she would say in response to your poem?” - became the guiding principle in composing the first half of Monster. That and a desire to somehow restore or make anew her humanity and honour in some way.

The Great Chain of Being

Baartman’s time in Europe coincided with the invention of race as a social construct that amplified the ideas of The Great Chain of Being (pictured above), which dates back to Aristotle and came to prominence with the Elizabethans, and which ranked all matter and life in a hierarchy starting with God at the top, progressing downwards through angels, humans, animals, plants and minerals. Within the category of human, there were sub-categories of hierarchy, later ratified by the scientific racism engendered by Carl Linnaeus’ categorisations of all humans, that placed black people below all the other races and just a rung above the orang-utans on the chain. It is into this ideological ferment that the systematic, phenotypic and sexually pathologised constructions of the inferiority of black women’s bodies that still occur today, connecting the perception of black women in in the 21st century directly to a historical precedent in the form of Baartman and the black woman in Christiaen van Couwenbergh’s painting.

Sarah Baartman’s Death and its aftermath

Before being dismembered by Cuvier and his assistants, Sarah Baartman had already undergone during her lifetime a “spiritual dissection” under the ravenous and devouring gaze of the coloniser. Her skeleton and a full plaster cast of her figure were exhibited in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris until the 1970s and her brain and genitals conserved in a jar. In effect, Baartman became a sculpture in death, displayed as both a living ethnographic subject and medical object. All of this inspired my prose-poem 1810 - 2002 in Monster, which also incorporates the journey of Baartman’s remains back to South Africa in 2002 after a campaign by Nelson Mandela.

The images in below in this section show Baartman’s skeleton being unpacked in South Africa, her coffin carried by her Gonaqua tribesmen pallbearers and the hill top on which she was buried. Above is the plaster cast Cuvier made of her figure. There’s a cloth wrapped around the cast’s hips in this photograph but its modesty wasn’t always so protected when it was on display in the Musée de l’Homme.

The museum’s stated mission, below, is negated by how it treated Sarah Baartman’s remains:

To display rare and beautiful things

gathered from the far reaches of the world

in a learned manner

in order to educate

the eye of the beholder

During her lifetime, Sarah Baartman captivated scientists, scholars, artists and writers as she continues to do today. Two men who were indirectly and directly instrumental in forging the perception of Baartman in the Western gaze and who stoked the fires of scientific racism are Carl Linnaeus and George Cuvier. They are so celebrated that statues of both of them form part of the facade of the Royal Academy of Arts at its Burlington Gardens entrance. I’ve always entered the Royal Academy of Arts through its Piccadilly entrance and had no idea there was another, opposite entrance in Burlington Gardens. I was startled to not only discover this other entrance but was even more so to stumble upon statues of these two men, who rightly shouldn’t be given such prominence in our modern, more tolerant society, effectively propping up the building (see image below). And only a stone’s throw away from where Sarah Baartman was first exhibited in London at the Criterion Building (housing Lillywhites sports goods shop down the road). As I have said, Sarah Baartman’s story is also a London story.

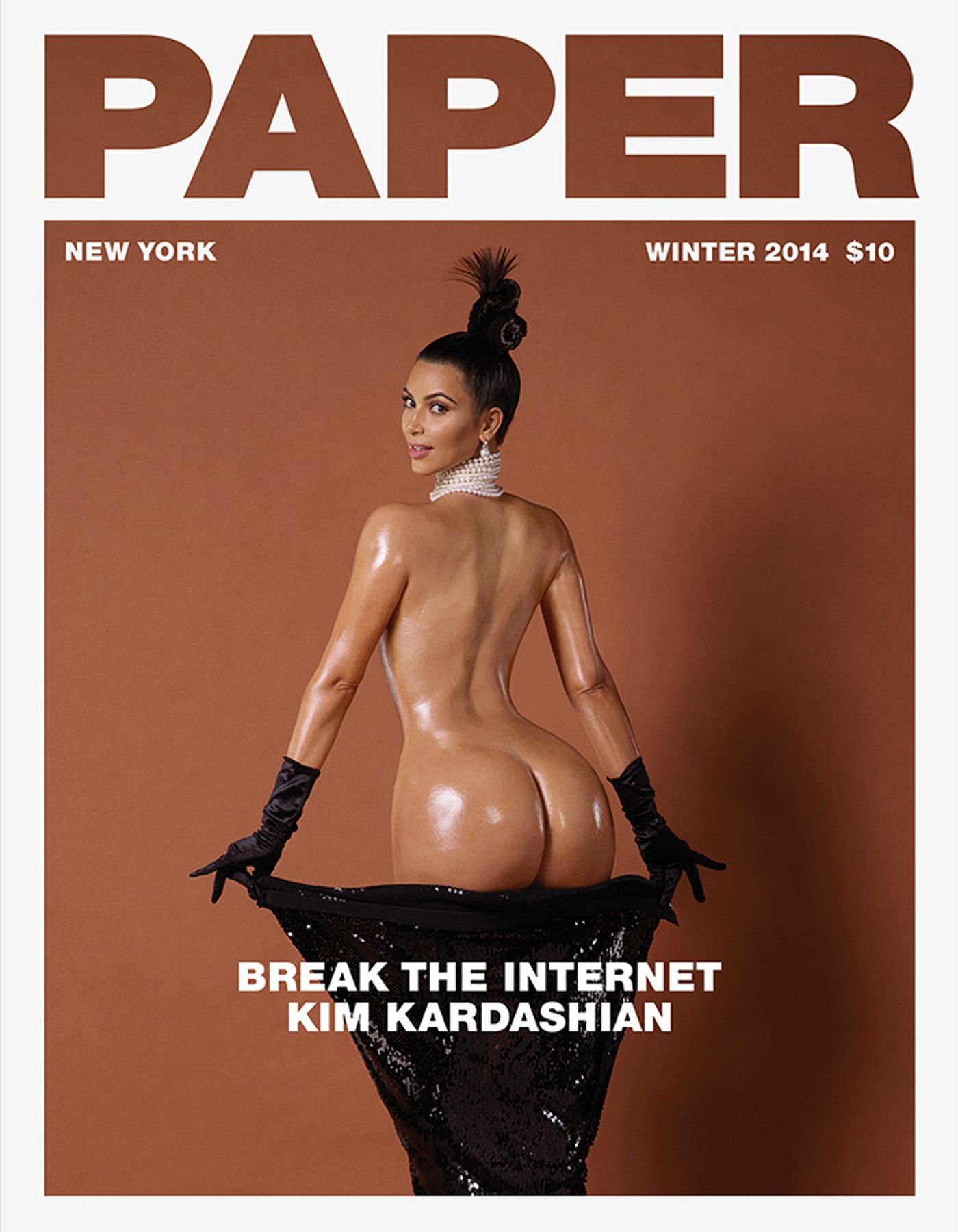

The objectification, appropriation, caricaturisation and fetishistic fascination with black women’s bodies perhaps reached its apotheosis in the figure of Kim Kardashian on the cover of Paper magazine. It could argued that representation of the black female body has come a long way its spectacle and vilification in the past to one of celebration in the present. If that’s the case, what are we to make of the fact that Kardashian got rid of her buttock implants as soon as they had served her purpose? Modernity presents a paradox because black women’s bodies only seem to be now celebrated when adopted by whiteness such as that of the Kardashian sisters co-opting of black women’s bigger bottoms, bigger lips and cornrows.